Nestled within the azure embrace of the Adriatic Sea, the Kornati National Park is a breathtaking tapestry of history and cultural significance. This captivating archipelago has witnessed the ebb and flow of civilizations, each leaving an indelible mark upon its rugged terrain and beautiful waters. In this blog post, we embark on a voyage through time, unearthing the Kornati Islands’ Neolithic relics, the legacies of the Illyrians and Romans, and the transformative impact of the Croatian arrival. We explore the medieval revival of the Venetian and fishing legacy, the islands’ population transition, and the emergence of a tourism-driven economy. Finally, we delve into the establishment of Kornati National Park, celebrating its enduring spirit of preservation and resilience.

Content

Discovering Neolithic Relics on Stranžica Hill

Iron Age and the Illyrian Legacy

The Impact of Croatian Arrival

Medieval Revival: Venetian and Fishing Legacy

Shifting Tides: The Kornati Islands’ Population Transition in the 17th-19th Centuries

Ownership Shifts: A Glimpse into Late 19th Century Kornati Islands

From Agricultural Roots to a Tourism-Driven Economy in the 20th century

From Proposal to Preservation: The Establishment of Kornati National Park

Discovering Neolithic Relics on Stranžica Hill

Archaeological findings at the foot of Stranžica hill on Kornat island reveal the early human presence in the area, dating back to the Neolithic era.

Iron Age and the Illyrian Legacy

Throughout the Iron Age, the Kornati Islands witnessed their initial verified settlement by the ancient Illyrian tribe known as the Liburnians. Traces of small quadrangular dwellings and hillforts across the islands suggest the Kornati Islands’ strategic significance. The islanders practiced animal husbandry and fishing, forging a sustainable livelihood in this picturesque environment. Liburnians, renowned for their remarkable mastery of the seas, left an indelible mark on the region’s maritime heritage.

During the Iron Age, an intriguing series of stone piles marked the landscape. Over the years, many of these ancient formations have been excavated in search of valuable artifacts. One particularly impressive stone pile can be found perched on Kravjak hill, nestled between the picturesque coves of Kravljačica and Tarac on Kornat Island.

In the mysterious realm of these enigmatic structures, it seems plausible that they served a variety of purposes, from somber funerary rites to fortified bastions or vigilant lookout posts. The deliberate positioning of these stone heaps upon the crests of hills evokes the notion that they may have acted as beacons for ancient mariners, skillfully navigating the perilous waters that surround the Kornati archipelago.

Hailing from the Iron Age, the Liburnians flourished as a distinct tribe, their legacy enduring until their ultimate absorption into the vast Roman Empire.

Roman Legacy in Kornati

The Romans, too, found the Kornati Islands intriguing. They constructed Villa rusticate and a fish pools, effectively severing the Liburnians’ unique living space between Kornati and Dugi Otok. Sunken piers, harbor facilities, and saltworks are remnants of the Roman presence in Kornati.

Byzantine influence in Kornati is marked by Tureta Fort on Kornat Island. The enigmatic Tureta fortress, nestled above mysterious remnants near an ancient church, might have been a monastery fort in the past, according to Dr. Irena Radić Rossi and Dr. Tomislav Fabijanić of the University of Zadar. These dual-purpose bastions protected both inhabitants and resources, offering refuge and sustenance. With its strategic location, the Tureta fortress could guard against threats from land or sea, maintaining a watchful eye over its surroundings.

The Impact of Croatian Arrival

With the arrival of the Croats to the Adriatic, sweeping demographic shifts unfolded across the islands, and the Kornati archipelago was no exception. The invading Croat forces drove the Roman population from the mainland, compelling them to seek refuge on the scattered isles.

However, the sea’s protection proved fleeting as the Croats soon encountered the ambitious Venetians, who sought dominion over the Adriatic. This pivotal epoch—marked by the decline of Byzantium, the ascent of Venice, and the Croat’s incursion into the Adriatic—had profound implications for the Kornati’s inhabitance. Amidst this tumultuous climate, the Kornati became unstable, likely devoid of permanent residents until the 13th century.

Medieval Revival: Venetian and Fishing Legacy

Medieval records reveal the Kornati Islands as a haven for herders and peasants. The islands’ strategic value blossomed amid the rising Turkish threat on the mainland and an expanding fishing economy. The Middle Ages saw Kornati’s revival, as evidenced by several culturally significant structures. The little church of St. Marry in Tarac, the salt warehouse, and the sunken remains of a salt pan in Lavsa Bay date back to this period.

However, in this epoch, the most captivating tales are woven around the thriving fishing industry. Tucked away on Dugi Otok Island, the venerable fishing port of Sali ascended to prominence as a leading fishing hub in the Adriatic, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the esteemed Vis and Hvar, attributed mainly to the bountiful waters of the Kornati Islands. Throughout this period, the skillful fishermen of Sali reveled in the exclusivity of their fishing rights in the Kornati domain, forging a distinctive maritime tradition that became an integral part of the region’s rich tapestry of history and culture.

A pivotal moment occurred in 1524 when a novel sardine fishing technique—using lamps—captured the region’s interest.

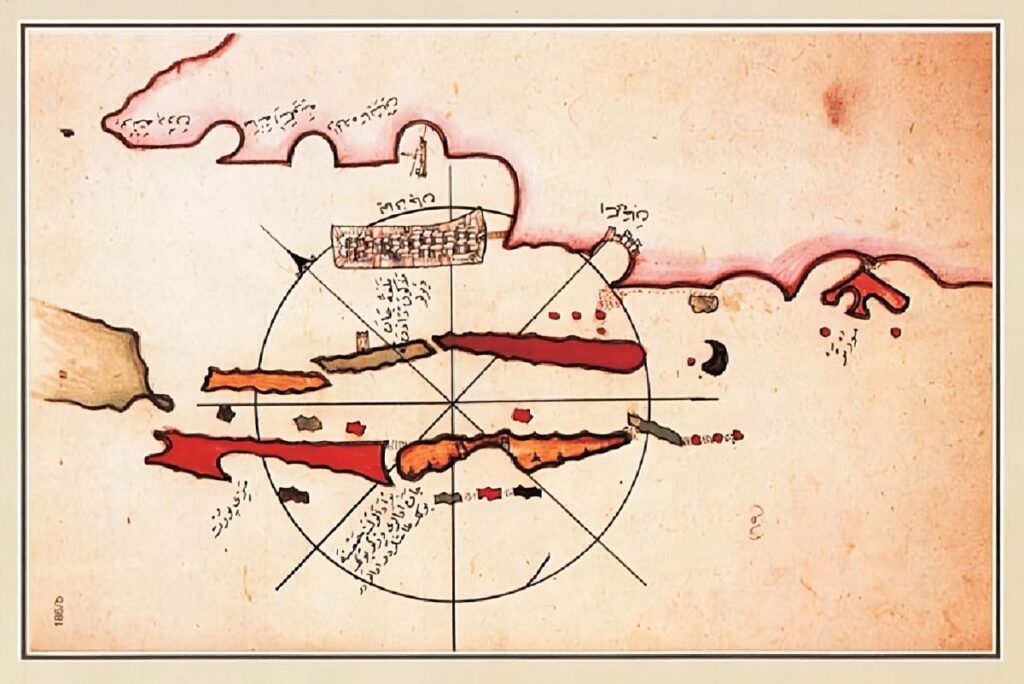

As the 16th century dawned, the Venetian authorities constructed a fortress on the islet of Vela Panitula primarily to collect taxes from the Kornati fishermen. In 1532, fishermen were ordered to deliver their catches to Vela Panitula for taxation.

A bustling fishermen’s settlement materialized in the shadow of the fortress on the island of Piškera (Jadra). The enterprise was an impressive undertaking for the era, boasting 36 huts, warehouses, eight docks, and a movable bridge connecting Piškera to Vela Panitula. Within the settlement, a small, single-nave church showcasing Gothic architectural elements was built and consecrated in 1560. During the summer “dark” (new moon), the settlement teemed with life as fishermen pursued pelagic fish like sardines.

However, when the Venetian Republic fell at the end of the 18th century, the fortress and Piškera settlement were likely abandoned swiftly. Today, only faint remnants of the fishermen’s village and the fortress remain visible, and the colony has vanished entirely. Only the restored church stands even now as a testament to its past.

Shifting Tides: The Kornati Islands’ Population Transition in the 17th-19th Centuries

From the 17th to the 19th centuries, the Kornati mainland saw a transition in its population.

The serfs, who once worked for the Zadar nobility, turned to new activities and areas, making way for settlers from Murter, Betina, and Zaglav. These new colonists, tenants of the Zadar nobility, sought additional living spaces due to overcrowding on their home islands.

First documented in 1627, the Murterini—residents of the island or village of Murter—found their way to the Kornati Islands as the population on Murter burgeoned, driven in part by refugees fleeing the Turks on the mainland. The island’s limited resources struggled to support this influx of inhabitants. At the time, two distinct groups emerged within the Kornati population: Murter-based peasants and shepherds and fishermen hailing from Sali.

During this era, the first rural complexes, known as “stanovi,” were established along the edges of the Kornati fields. These dwellings housed the peasants and shepherds from Murter. Cadastral maps between 1824 and 1830 reveal that 187 colonists resided in the village of Murter. During that time Murterini and Pašman Island residents were at odds with the fishermen of Sali. The disputes over fishing rights in the Kornati only intensified over time.

It is worth noting that during this period, the Kornati landscape faced an accelerated and relentless process of deforestation. A pivotal moment occurred in 1850 when a ferocious wildfire blazed for forty days. The inferno eventually engulfed the island of Kornat, decimating the last remnants of its once-lush forest.

In the spirit of time-honored traditions, the Kornati landscape has been shaped by the deliberate burning of overgrown grasslands. This ancient practice of pasture maintenance has given rise to the occasional wildfire. As a result, the Kornati terrain has been stripped bare, ultimately evolving into the stark yet captivating scenery we witness today.

Ownership Shifts: A Glimpse into Late 19th Century Kornati Islands

As the 19th century drew to a close, the Zadar nobility, who then owned the Kornati Islands, struggled to pay taxes and duties due to new agrarian policies in Dalmatia. Consequently, they sold off the islands.

In 1885, the Murterini purchased the island of Žut. In 1896, they joined forces with the people of Betina and Zaglav to acquire the island of Kornat and its associated islands.

Thus, the residents of Murter and neighboring islands became the new owners of over 90% of the Kornati mainland.

Meanwhile, the people of Sali continued to focus on the sea, holding on to their traditional and documented fishing rights, which have played a significant role in the islands’ history.

From Agricultural Roots to a Tourism-Driven Economy in the 20th century

The turn of the 20th century marked a significant shift in Kornati’s economy and way of life. Agricultural activities peaked, with a tenfold increase in arable land and the construction of an intricate network of dry stone walls. Life gradually moved from the island’s interior to the coast, with ports and settlements in favorable bays gaining importance.

As the sun set on traditional economic activities from the 1920s, the Kornati archipelago’s landscape remained adorned with the legacy of approximately 18,000 olive trees scattered across extensive groves and a striking network of 323 kilometers of dry stone walls.

With the winds of change, tourism began to sweep across the islands, emerging as the dominant economic force in this enchanting paradise. The growth of tourism has been a tale of both opportunity and challenge, as the region witnessed a greater number of houses built in the last 70 years than in its entire previous history. In the midst of this delicate balance, the Kornati Islands continue to embrace their past while looking forward to a vibrant and ever-evolving future.

Tourism manifests itself in various ways on the islands, including the establishment of restaurants that showcase local cuisine, accommodations for travelers seeking a serene getaway, a thriving nautical tourism sector catering to sailing enthusiasts, rent-a-boat services that allow visitors to explore the islands independently, and excursion boats that offer guided tours of the picturesque archipelago. These developments have diversified the local economy and created new avenues for visitors to experience and appreciate the unique beauty and culture of the Kornati Islands.

Nestled within the rich tapestry of the Kornati Islands, the fusion of agricultural traditions and burgeoning tourism provides the present-day custodians – with a unique opportunity to cultivate a blended, forward-thinking approach to their tourist-agricultural offerings. As young maritime entrepreneurs, proprietors, restaurateurs, fishermen, and sheep breeders embrace the National Park’s esteemed brand, they embark on a quest to forge a sustainable future, nurturing the hope that their innovative endeavors will create lasting value and bestow an enhanced legacy upon the generations to come.

From Proposal to Preservation: The Establishment of Kornati National Park

The first written proposal to establish Kornati National Park emerged in 1965, in Sven Kulušić’s article “Kornati Island Group.” The Executive Council of the Parliament of SR Croatia, In 1967, declared the Kornati Islands and the southeast part of Dugi Otok Island with Telašćica Bay as natural area reservations, granting them essential protection. In 1976, a study proposed a Spatial Plan for particular purposes, outlining the creation of a national park in the region.

Kornati National Park was officially established by the Parliament of SR Croatia in 1980, including the Lower Kornati and the southeast part of Dugi Otok Island with Telašćica Bay.

In 1988, due to divergent management approaches, the park was split, with the northwest part becoming Telašćica Nature Park and the more significant portion in Šibenik-Knin County retaining its status and name as Kornati National Park.

In conclusion, the Kornati National Park, as we know it today, stands as a testament to the delicate dance of coexistence between humans and nature throughout the centuries. The islands’ inhabitants, particularly the Murterini, have left indelible marks on the landscape—cultivating pastures, constructing dry stone walls, nurturing olive groves, and building humble port villages. The park’s history encompasses eras of Neolithic origins, Illyrian settlers, Roman exploits, and the influences of Croatian and Venetian powers. The transition from an agricultural society to a tourism-driven economy in the 20th century reflects the adaptability of the communities that have inhabited the Kornati Islands over time, bringing both prosperity and challenges. Today, the park serves as a living museum of the Adriatic’s rich cultural heritage and history, inviting visitors to journey through time and discover the profound connections between humankind and the natural world.